The Architecture of Lakki — Bold, Bizarre and Forgotten

It’s one thing to stumble across a building that has slipped under the radar of time and recognition. It’s quite another to uncover the rich and fascinating architectural history of an entire, virtually forgotten town on a Greek island. Lakki is located on Leros in the Greek Dodecanese, just off the coast of Turkey and at first glance it reveals itself to be unique and even bizarre.

I have been coming to Leros for more than twenty years and Lakki has always fascinated me. The rest of the island offers up the quintessential architecture and history that one generally associates with Greek islands. As you ride your scooter down towards the bay on which Lakki is located, you ease gently into a strange and unexpected urban landscape. Your architectural and urban design eye is confused and amazed as you try to take stock of the place. The lines of the buildings are clean and curved and the street layout orderly and structured. You’re not quite sure where you are.

Let’s rewind to get some context. Leros and the other islands in the Dodecanese were liberated from Ottoman rule by the Italians in 1912, at the behest of Greece. The locals regarded it as liberation. But the Italians stayed awkwardly on and, with the rise of Fascism and Mussolini, they started hammering out their intentions around the Mediterreanean and beyond. In the Dodecanese it was Rhodes, Kos, Kalymnos and Leros. Further afield their colonial aspirations included Eritrea and Libya. While Asmara, Eritrea is a famous example of a new town in Rationalist-Fascist style — and now a UNESCO world heritage site — Italian efforts in Greece were primarily focused on buildings, some street redesign and lots of military facilities.

The bay on which Lakki sits is the largest natural harbour in the Eastern Mediterranean and positioned perfectly to avoid prevailing winds so it was an obvious choice for an Italian military base. The island was fortified heavily through the 1920s and 1930s and the naval base expanded exponentially. The site was also chosen as the location for one of Mussolini’s new towns.

In order to figure out why Lakki is so hard to decipher I enlisted the help of the local historian, George Trampoulis. I showed up unannounced at the local archive on a narrow street in the island’s old capital, Platanos but George welcomed me warmly. He is also a schoolteacher and politician on the island and has a contagious passion and energy for both the history and the future of Leros. I told him I wanted to hear more about Lakki and he promptly said, “meet me in front of the cinema at seven this evening and I’ll take you for a tour in my Porsche. Then tomorrow we can meet here at the archive to look at documents”.

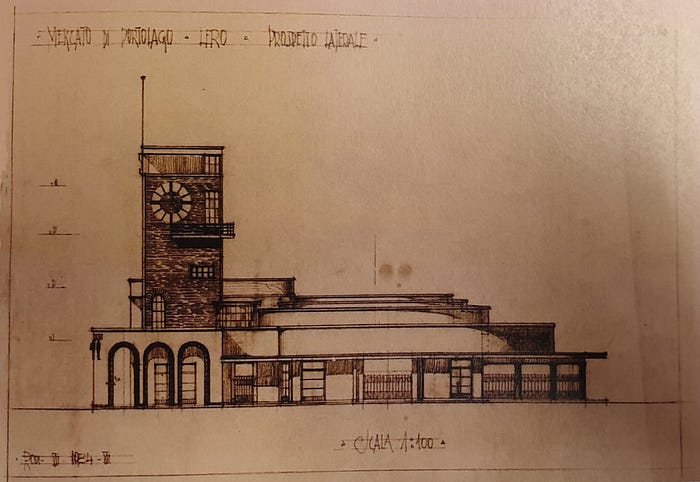

I’m not a car guy, but George rolled up on time in a beat up old car so far from a Porsche as you can get. “Nice ‘Porsche’, George”. He smiled and shrugged. “It’s got four wheels and a motor under the hood”. George and I would get along just fine. Off we went. Up and down the streets of Lakki, around the bay, into the hills to the north to look at the ruins of second world war installations. I would have to constantly try and reel George back to the story of Lakki from his otherwise fascinating narrative about the military history of the Italian occupation and the famous Battle of Leros in 1943. The book and film Guns of Navarone ended up being situated in Rhodes, but it was inspired directly by the fight for Leros and Lakki. The island is rich in second world war stories, with several shipwrecks that attract divers from around the world, but I was there to hear about urban design and architecture. “Okay, okay”, said George. During three hours at the archive the next day, we pored over blueprints, photos and documents and I while I started to get a clearer picture of the history of Lakki, I realised that there are still many unanswered questions.

George confirmed this. The archives are incomplete and many documents are possibly lost. In my own research prior to meeting him I could see that the narrative about Lakki is fragmented. Bits and pieces have to be strung together and some discarded. Even despite the sparse material available on the internet, the Italian name for Lakki — Portolago — is confusingly attributed to both the first governor Mario Lago and “port lake”, because the bay is calm, with a narrow entrance, and resembles a lake. George confirmed that the latter is correct.

Here’s what is certain. The Italians started work on establishing a naval base in 1923 and work on a new town across the bay began in 1928, lasting until the late 1930s.

This is where things get muddied. Why did work stop suddenly, leaving the town unfinished? One brief passage I found states mysteriously that “Lakki was built around wide boulevards by the engineers Sardeli, and Caesar Lois, an Austrian”. I’ve been unable to find any more information about these two or any dates relating to their work. Believe me, I’ve tried. Most of the design of the new town is attributed to two Italian architects, Rodolfo Petracco and Armando Bernabiti but the scope of their work is unclear. Their larger buildings are documented but little is known about how involved they were in the street design and layout or the smaller structures.

In looking for facts, I found myself becoming fascinated by these two architects. Little is known about them. Only brief entries on Italian Wikipedia confirm dates of birth and death and an incomplete list of the buildings they designed in the Dodecanese — on Rhodes, Kos and Leros . I can track Petracco to some extent but he never continued his prolific period in the region. He was commissioned to design a war memorial in Foggio, Italy in 1952, but that seems to be all. He died in his hometown in 1961.

Bernabiti was equally prolific in the region but he essentially dropped off the map after the war. There is no record of him working as an architect until his death in 1970.

Who were these guys? Buildings rose from their blueprints at a furious pace in Rhodes and Kos before they were handed a spectacular commission in Portolago. They devised and designed a new town virtually from scratch. Portolago was part of a grandiose plan to “Italianize” the region and by all accounts it was to play an important role as a military port to cement Italian domination and with room for a growing community of civilian colonists.

I saw the plans for water supply and sewers and they weren’t a closed system for a town of predetermined size but clearly positioned for expansion beyond the initial plans. Someone had grander designs for Portolago.

Many of Mussolini’s new towns were somewhat uniform in their design. There is some structure and pattern to Sabaudia, Aprilia, Mussolinia as well as the new towns in Eritrea and Libya.

Something different, however, happened on Leros. It’s as though Petracco and Bernabiti had other ideas. I can’t know the details about why they took Portolago in a different direction. Were they granted freedom to experiment by Rome? Unlikely, given the nature of dictatorships. Mussolini didn’t exert much influence of his architects until later in his reign, allowing the architects in the early 1930s to call their own shots. So perhaps Petracco and Bernabiti realised that Rome was far away — as were their architect peers — and more preoccupied with the attempted expansion of Empire than the plans for a provincial outpost. The military harbour was up and running and serving its purpose. The town across the bay was of lesser consequence.

I’d like to think that these two men thumbed their noses at the systematic design of the regime and used their isolation to begin designing the town in a more personal way. Experimenting with their own ideas about scale and form. The layout of the streets followed the Italian Fascist desire to emulate ancient Rome. Two squares — one on the harbour and another farther inland and both larger than you would expect — are linked by a straight street. Public space designed for Duce worship was a classic feature of new towns. But one of the first things you notice in Lakki is the scale. Other new towns like Sabaudia, in Italy, are grander and if you put some of the buildings from Italian new towns into Lakki, they would seem hopelessly out of place. The scale in Lakki is human, designed for a community rather than inspiring awe in an empire.

The harbourfront was straddled by the Custom House (Dogana) and the Fascist House — a standard feature in the age. The latter was bombed by the Greeks at the first opportunity, and fair enough. In the middle it’s the theatre and hotel forming the first visual impression, next to the “commercial zone” and backed by the beautiful public market. Even the state tobacco monopoly has a building in a prominent location. The primary school still performs the same function today and the areas designated for “palacini” — small palaces — which were homes for the officers are still in place around the central area, as well as a large hospital and a Catholic church.

There must have been a process to Petracco and Bernabiti dividing the buildings to design between them. They obviously knew each other as they began work in the town. Did they meet at a café and play backgammon to decide who got to design what? “Best two out of three for… the public market?” “Si, signore”.

Did they agree in hushed tones — over chilled glasses of ouzo in the sultry evenings — to depart from the strict form of the Rationalist — Fascist movement or did they just agree to give each other an espace libre — loosely following rules and adamantly pursuing personal desires?

Bernabiti, for one, departed from the decorative bling on his earlier buildings in Rhodes and Kos. Slimming down the look. Simplifying. But still staying within the boundaries of the goals of the regime. Both seem to tip their hat to the drawings of Giorgio de Chirico but again, without any solid reference.

What appears to be two personal journeys has resulted in an incredibly unique and charming place. They made a community — something architects are rarely good at. Another result of their freedom to design is that Lakki is hard to pin down with labels. In the few articles about the town’s history, a host of forms are mentioned, without any consensus.

Rationalist Fascist, Italian Rationalism, Mediterranean Rationalism, International Style, Bauhaus inspired, Art Deco, Italian Modernism, Streamline Moderne.

I like that. The architecture community is so keen at naming, labelling, categorising. Some Italians claim today that Lakki “is the same” as all the other new towns Mussolini commissioned. As though wanting to create a historical link with broad brushstrokes across the Mediterranean and Aegean seas and beyond into Africa — with all the awkward fascist sentimentality that that involves. But Petracco and Bernabiti would have it different. They might fancy the fact that what they created defies labels.

George puts it nicely: “They created something sweeter than Rationalism. They did it in the Lerian way”.

Now George is a Lerian and a proud one at that so of course he would like to think that the spirit of the island influenced the two Italians. Fair enough. But Lakki is, indeed, sweeter.

As I sat at a table at my favourite beachfront café researching and writing, I thought I’d enlist the help of a good friend — and the smartest architect I know — Dr. Steven Fleming. I bounced all my photos of the buildings over to him and he regaled me with a steady flow of architectural commentary of the individual buildings. He ended up with the same conclusion.

“It’s all a bit out of the box. I suppose if they had a free hand, a lot of buildings to do, and not that much time, it makes sense that they went a bit eclectic. I would.”

I fancy the idea of Bernabitian Petraccoism to describe the architectural legacy of the town but perhaps the work done in Lakki deserves to be called simply Rationalist Lerianism.

Today there are barely 2000 people living in Lakki. At its peak there were 32,000 — albeit many of them troops in barracks — and there was street life and culture. Over the past twenty years I have seen buildings restored — slowly but surely. Lakki still has the feel of a ghost town, even in high season, even though there are more cafés than ever. Increasing numbers of summer visitors ride bikes or scooters around town. Middle-Eastern and African refugees from the camp on the military side of the bay amble freely about, adding a cosmopolitan feel. The World War 2 museum is a draw, as well. The cinema has reopened and doubles as a concert hall. It’s taken 80 years for the town to begin to thrive again — however hesitantly.

George harbours a dream of getting UNESCO World Heritage status for Lakki but admits that much work needs to be done before they get anywhere near. The restoration would need to be completed before UNESCO bothers to look at it. Given the state of the Greek economy, that won’t be anytime soon. Still, I see work done each time I visit. A tricky detail is that many buildings have been expanded with extra floors and additions, blurring the lines of authenticity. To be fair, quite a few owners through the decades have tried to be true to the original designs when adding on, which I find impressive.

The original plans for the whole town were never completed and the lines are blurred from street to street, as well. What is original and what is recent? Where does the vision of Petracco and Bernabiti end and the later work of Lerians begin? This only adds to the charm of the town.

Speaking to Lerians through the years, I can ascertain that they have long considered Lakki to be an oddity. A weird relic of the awkward past that wasn’t really understood and rather ignored. Only a quarter of the population of Leros live there and because of the spacious streets, it always feels empty compared to the tiny, winding streets of the other towns on the island. One might expect that through the decades anonymous structures would have been slapped up and historical integrity compromised in the name of cheap buildings. The island mayor is locally infamous for ignoring the town of Lakki due to the fact — if you believe the heated political chats I’ve had with locals at cafés — that he has business interests in the “tourist typical” towns on the island.

As George puts it: “People on the island generally say it’s a beautiful town but have largely ignored it. Only recently have they discovered they have a small treasure”.

There has been an upgrade of the port to accommodate sailboats so more people are discovering Lakki. There is more to Leros, absolutely. That’s why I keep coming back. It’s not like other Greek islands. What it lacks in pristine beaches it makes up for with being rough, raw and authentic. There is WW2 tourism, diving, sailing and the general Greek lifestyle.

But Lakki is a monument, however undefined, to an architectural era, however fleeting. It is also a monument to the vision of two forgotten architects who seem to have defied a regime in their personal quest for “something sweeter”.

See more photos in this Lakki Architecture album on Flickr.